I grew up in Chicago, and it’s history is steeped in architecture. Most notable for the history of urbanization is The Chicago School of Architecture, which evolved in response to the new technologies for buildings in the late 19th Century (involving steel-frame construction and elevators, which allowed for progressively taller buildings). Chicago became the architectural city of the time because of the buildings that boasted the latest innovations in form and height were being erected in the city. The main practitioners of this style were Daniel Burnham, Louis Sullivan, William Holabird, Dankmar Adler, William Le Baron Jenney, John Root, Martin Roche, and Solomon Beman.

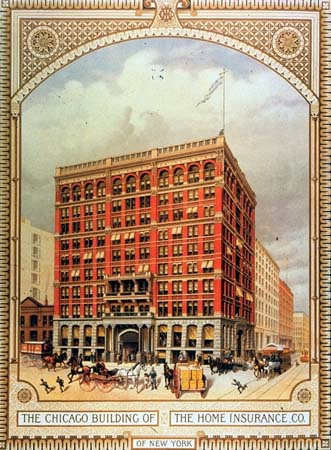

For example, the Home Insurance Building (1883-85) was one of the incremental steps to a complete iron skeletal framed building. Still using masonry construction, William Le Baron Jenney encased the iron supporting walls in stone. This building is the first skyscraper in existing structural terms. Starting less than a decade later, the Reliance Building (1889-91) by Burnham & Root was underway. This trumped the Home Insurance Building in the movement toward austerity and Modernism; it was the “quintessential expression of the steel frame.” Visually, the heavy masonry was nearly eliminated; leaving the upper floors covered with white glazed terra cotta and large ‘Chicago style’ windows. The lightness and sixteen-floor height of the structure come from an emphasis on verticality.

The next vast step in city forms came with the striking Modern and International styles. The Feb. 22, 1932 article called “Machines to live in” in TIME Magazine explained the emergent style of International Architecture:

"If the average citizen does not understand the principles of the International Style in architecture the fault is not with its innovators. France's Le Corbusier, most vocal of the lot, has expressed it in a single sentence: ‘The modern house is a machine to live in.'

Like all good architecture, the International Style demands that the new materials at the service of modern architects (reinforced concrete, plate glass, steel, etc.) shall be used honestly. Cement walls must look like cement walls and not be disguised as Gothic masonry.

The International Style thinks of building in terms of space enclosed as opposed to mass. Walls no longer support the house; they are curtains enclosing its skeleton.

The International Style as opposed to "modernist" architecture eschews all decoration and ornament. "Functionalism" (a word overworked ad nauseam) is its watchword. Such beauty as their buildings possess is dependent on fine proportion of individual units, clever use of color, and the technically perfect use of materials. (Cement is sometimes poured in glass-lined forms to give it a marble-like polish.) Light is its fetish."

Like all good architecture, the International Style demands that the new materials at the service of modern architects (reinforced concrete, plate glass, steel, etc.) shall be used honestly. Cement walls must look like cement walls and not be disguised as Gothic masonry.

The International Style thinks of building in terms of space enclosed as opposed to mass. Walls no longer support the house; they are curtains enclosing its skeleton.

The International Style as opposed to "modernist" architecture eschews all decoration and ornament. "Functionalism" (a word overworked ad nauseam) is its watchword. Such beauty as their buildings possess is dependent on fine proportion of individual units, clever use of color, and the technically perfect use of materials. (Cement is sometimes poured in glass-lined forms to give it a marble-like polish.) Light is its fetish."

The aesthetic of this and Modern Architecture were totalizing and were explicitly aimed at creating universal forms. They eschewed not only “all decoration and ornament” for pure functionalism, but also any indigenous or localizable style.

This avant-garde aesthetic was not only anti-traditional, but it was anti-sustainable in aesthetic parameters and in philosophical foundations. There is a binary between Traditional and Modern/Inernational styles. Where Traditional is place-centered, the Modern** style is universalizing and effectively place-blind. Traditional uses local materials and is often inherently sustainable. Modern uses primarily concrete, marble, glass and steel often (if not always) regardless of a material source’s proximity to a site. In sum, the Modern aesthetic philosophy affords no concept of sustainability because of its ideological and formal limitations; the skyscraper must adapt to this challenge.

The aesthetic drive for Modernism segued into air conditioning, which was called 'man-made weather' by its inventor. The implementation of this invention effectively divorced architecture from nature. Paradoxically, this divorce took place in the context of the Modern movement, which also upheld ‘truth to materials’ and formally expressed its love of natural light. Corbusian ethics, in particular, were so pro-machine that they were antithetical to environmental—or even nature-aware—architecture.

Perhaps the man with the most recognized name in Chicago Architecture (if not the practice as a whole) is Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright approached the task and art of architecture unlike most others of the 19th century. He looked at nature to inspire his designs, (as many others indisputably did), and he had a distinctive way of conveying his aesthetic visions. The theme of inclusion was present in the layout: Wright created interwoven spaces, culminating in an open-plan with a characteristic central fireplace mass. Openness was important on the exterior as well, as Wright’s Prairie Style house opens into and interacts with the landscape through views, porch spaces, horizontal emphasis, cantilevers, outdoor walkways, patios, etc.

Wright’s Robie House (1906-09) has been praised from all corners of the globe, and was even nicknamed in Europe as the “ship house” for its shape after Wright published his portfolio in Berlin. Robie house was called the “culmination of the Prairie Style” because Wright had been refining the Prairie aesthetic, but the houses previously had not encompassed all of the principles fully. Robie is unified throughout with carpet, furniture, and integrated light fixtures created by Wright, himself. Though Wright did not aim for sustainability (in our contemporary definition), his design aesthetic and philosophy were (in juxtaposition to the Modernists), naturally inspired; they were the Prairie of the city.

The Robie House is notable for all the Prairie principles, but especially its hyper-emphasized horizontal planes and eaves, as none of Wright’s designs had done to such a degree before. Overall, Robie house was the climax of Wright’s search for “Nature…not ready-made [but] a practical school beneath…in which a sense of proportion may be cultivated” within the Prairie Style. This style did not employ any ‘green’ technologies, per se, but it did propose a naturally inspired, total viewing model.

Works Cited

*Home Insurance Bldg image from http://www.arthistory.upenn.edu/spr01/282/w2c2i04.jpg

**For the purpose of this blog entry, I intend to encompass both Modern and International styles when speaking of the "Modern."

David Gissen, ed., Big and Green: Toward Sustainable Architecture in the 21st Century, (New York: Princeton Architectural Press), 116

"Machines to live in” Feb. 22, 1932. TIME Magazine. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,743212,00.html.